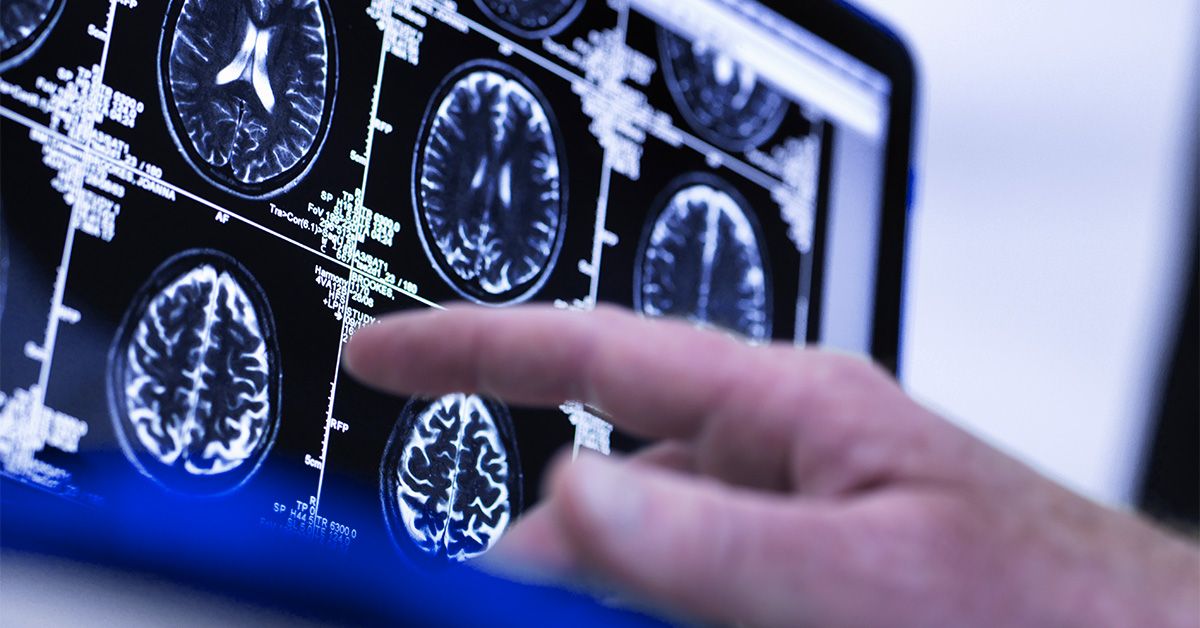

An Experimental Brain Scan May Predict Age-Related Disorders

Dr. Maxine Hart sat in her dimly lit office, poring over the results of a groundbreaking study that promised to redefine our understanding of aging. She had spent years researching the physiological and psychological dimensions of aging, but the findings from a collaborative effort between researchers at Duke, Harvard, and the University of Otago were nothing short of revolutionary. A simple brain scan conducted around age 45 could potentially predict how quickly someone ages—both mentally and physically. The implications for healthcare, lifestyle choices, and even public policy were staggering.

The Landscape of Aging

Aging is notoriously complex. While genetics account for approximately 25% of variances in longevity, lifestyle choices play a predominant role. Factors such as diet, exercise, and stress management can significantly influence how quickly individuals experience age-related decline. A person’s biological age—how old their cells are—often diverges from their chronological age, complicating existing frameworks for understanding health risks.

In a recent study published in Nature Aging, researchers unveiled the Dunedin Pace of Aging Calculated from NeuroImaging (DunedinPACNI), a predictive model that links brain health to overall aging trajectories. “This model is a significant leap forward,” stated Dr. Oliver Rhodes, one of the principal investigators of the study. “It gives us the ability to assess biological age simply through a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which is a non-invasive method.”

The Dunedin Study: A Foundation for Change

The DunedinPACNI method builds upon existing data from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a pioneering longitudinal research initiative tracking 1,037 individuals from birth through adulthood. Researchers measured various health markers—including blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and physical capabilities—over several decades, ultimately identifying patterns that correlate with aging.

- Gait speed.

- Strength and coordination.

- Cognitive function metrics.

- Self-reported health status.

- Visible signs of aging.

“The original Dunedin Study has provided invaluable insights into how various elements of health interact as we age,” Dr. Hart explained. “By incorporating MRI technology, we can now add a profound layer of understanding.”

How DunedinPACNI Operates

Using data from an MRI scan taken at age 45, researchers could create a score that effectively predicts an individual’s aging rate. The results showed a high degree of reliability compared to more established measures, including epigenetic clocks based on gene methylation. “The predictive accuracy we observed was astounding,” commented Dr. Emma Linton, a neuroscientist unaffiliated with the research. “These scores correlated closely with measurements from other well-established biomarkers.”

Participants with faster DunedinPACNI scores exhibited numerous indicators of accelerated aging, including:

- Weakened balance and slower walking speeds.

- Increased physical limitations and lower self-reported health.

- Subpar performance on cognitive assessments.

- Enhanced risks of cognitive decline from childhood through adulthood.

- Older physical appearance reported by the subjects themselves.

Broader Implications for Health and Policy

The implications of this research stretch beyond individual health assessments. “If we can identify people at risk of age-related disorders earlier, we can potentially enact lifestyle changes that could prevent or delay the onset of diseases like dementia and cardiovascular problems,” noted Dr. Hart. She emphasized the social importance of metrics that reflect not just the aging process in isolation but as part of a systemic view of health.

Emer MacSweeney, an expert in neuroradiology, pointed out the capacity for this research to influence clinical practices. “Using MRI scans to not only detect diseases but to track aging allows for proactive health management,” she told us. “Understanding aging as a dynamic process opens up avenues for public health interventions.”

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the DunedinPACNI tool is not without limitations. Questions remain regarding the applicability of the findings across diverse populations. Dr. Hart cautioned, “The model was trained primarily on participants with European ancestry, and its effectiveness in younger or more ethnically diverse cohorts remains to be validated.” Additionally, the model infers dynamic aging processes from a static snapshot, which might not capture multifaceted changes over time.

“While we’ve seen impressive results in data from multiple large datasets, broader validation is essential,” Dr. Linton iterated. “The potential for this research to shake up how we view aging is monumental, but we need more evidence to warrant its clinical application.”

In a world increasingly concerned with health span and longevity, the DunedinPACNI model stands as a beacon of promise. As society grapples with an aging population and its subsequent challenges, this pioneering effort seeks not just to understand the aging process but to empower individuals to take proactive measures for healthier, longer lives. While the road ahead requires careful navigation and validation, the prospect of leveraging a simple brain scan to gauge the intricacies of aging is exhilarating, offering hope for a future where knowledge truly translates into better health outcomes.

Source: www.medicalnewstoday.com